Professor Christopher Robichaud.

Over five weeks I took part in ‘Leadership and Character in Uncertain Times’, a Harvard Kennedy School executive course. The course was all online and took place in the middle of the night (on Eastern Standard Time) with live seminars twice a week, group work once a week and a series of videos and readings assigned weekly. The course focussed on how leaders navigate personal values with community values, within varying parameters of authority, during times of uncertainty and instability. Each week built further on an adaptive leadership model (discussed in week one), mixing ethics with behavioural science, evolution with politics, and exploring the grey, uncomfortable areas of adversity and division within today’s world. We applied a number of leadership frameworks and tools to modern case studies, including gender bias within the workforce and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The course was led by Christopher Robichaud, Senior Lecturer in Ethics and Public Policy, who ran the online sessions with our cohort made up of over 100 individuals from 23 countries. The content was often challenging, sensitive and polarising, discussing social and cultural issues that often see people sitting at two ends of a spectrum. The goal of the course was to engage with and consider a wide range of tools and frameworks, looking at what defines a leader, the kinds of challenges they face and how to lead with integrity in the face of disharmony and polarisation.

Each week covered a different topic; I highlight some key takeaways from each week below.

Week 1: Adaptive leadership framework

The first week laid the foundations of the course, first exploring moral leadership as a concept and how this relates to the adaptive leadership framework.

Professor Robichaud first defined morality as being the set of principles and values that arise in three separate moral contexts:

- Personal context (what principles guide your own thinking and decision making;

- Cultural context (what values guide your community); and

- Organisational context (values within an organisation/institution you operate within – what you are authorised to do from the standpoint of your organisational beliefs and values).

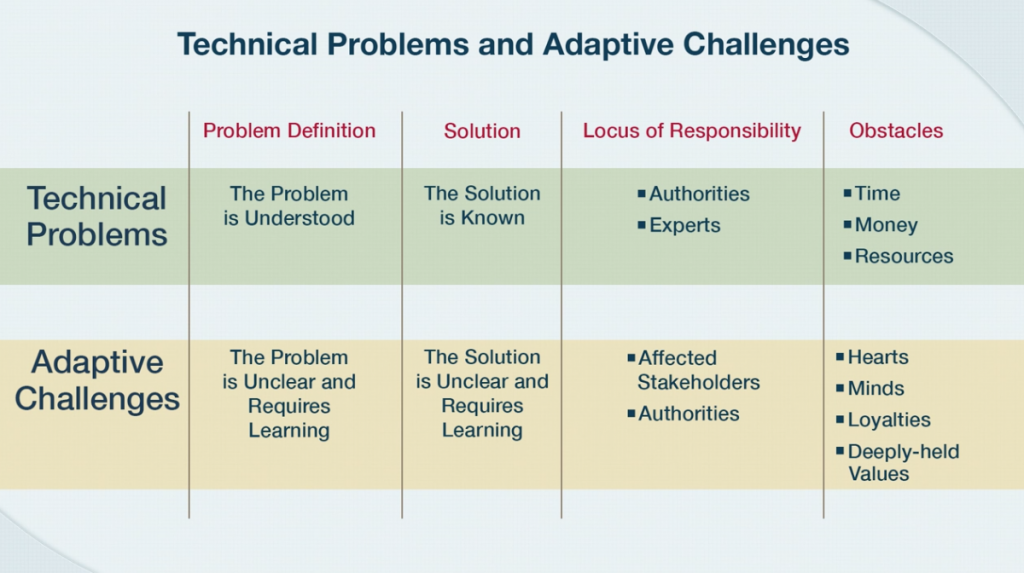

Leadership is then discussed as an activity or an approach to dealing with adaptive problems. The framework separates technical problems from adaptive problems:

- Technical problems are those that are clearly understood, in which the solution is known, the mechanisms to overcome these problems are known, and the required expertise/knowledge are known.

- Adaptive problems are those that are much more complex, the solutions are unknown, the mechanisms are unknown and the problem requires interrogation, inquiry, critical thinking and the flexibility for trial and error.

Image taken from a video presentation by Professor Robichaud.

Leadership when engaging with an adaptive problem therefore requires someone who is able to navigate this unknown territory and its moral complexities, taking into consideration the three moral contexts discussed above. Adaptive leadership involves developing a comfort with complexity and accepting that not everyone will always agree on what ought to be done. It is defined in week one as:

- Supporting others to work on adaptive/technical problems

- Mobilising people to make progress on adaptive/technical problems,

- Embracing ambiguity; and

- Interrogating problems and accepting their complexities.

Leadership was also defined as separate from authority with authority being broken down into two types:

- Formal authority is described as a position/role that is formalised, from which you are able to make decisions within the limits of the role.

- Informal authority is derived from establishing oneself within a community or group which enables you a platform to make decisions within the limits you have been entrusted with.

Case study 1:

Leadership and authority were separated this week in order to distinguish the fact that people in authoritative positions are not automatically leaders. This idea was interrogated through a case study on the story of Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize-winning human rights activist in Myanmar, who then later became the civilian Head of State and became known for exacerbating and covering up the Rohingya Muslim crisis. In her position of informal authority, she became a symbol for peace and unity, however, when she took on her political role, she was heavily criticised internationally, and received widespread outrage for her dealing with Rohingya Muslim’s in Rakhine State. This case study helped identify the limits placed around formal positions of authority, misguided expectations that authorities will always (or never) exercise leadership, how authority can inhibit leadership, and how, when posed with an adaptive problem like the Rohingya Muslim humanitarian crisis, leaders of a country often fall short of global expectations.

Week 2: Moral narratives

The second week explored personal moral narratives, combining superheroes with ethical theory. Superheroes and the trials and tribulations they meet in their journeys often depict a moral decision they must make that then defines their character. An example used was when Spiderman had to make the decision between saving his one true love, Mary Jane, or a train carriage full of children. These moral narratives explore the concepts of good and evil, right and wrong, and encourage viewers to ask themselves ‘what would YOU do’? Through superhero themes we explored the ethical concepts of utilitarianism and deontology. This week was designed to explore the ‘original you’, to find out what your core beliefs are, where your lines of ‘uncomfortability’ are drawn, and how your core principles drive decision-making. During group work we were asked to share fictional sources that assisted us in thinking about leadership and character, discuss the life story of someone that assisted us in thinking of leadership and character, and then dive into our childhood and past experiences to understand how these may have shaped our moral foundations.

Week 3: Negotiating community values

Week three focused on community values, bringing back the key understanding that in any society, reasonable people may not always agree with one another. We explored why it is that people with opposing views often find it so difficult to relate to one another. The framework discussed was Jonathan Haidt’s five moral foundations, which can be used to understand personal and community values and why it can be hard for individuals to objectively consider different values as anything but wrong or even dangerous. The five moral foundations framework suggests that there are five innate ‘pillars’ of morality that we are all born with and that, over time, we adapt and refine these through culture and experience or nature vs nurture. These moral foundations can be seen to have evolved out of response to adaptive challenges when humans first began living in larger communities. These five foundations are:

Foundation 1: Care/harm

This evolved out of caring for vulnerable children. It makes us sensitive to signs of suffering and need; it makes us despise cruelty and want to care for those who are suffering.

Foundation 2: Fairness/cheating

This evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of reaping the rewards of cooperation without getting exploited. It makes us sensitive to indications that another person is likely to be a good (or bad) partner for collaboration and reciprocal altruism. It makes us want to shun or punish cheaters.

Foundation 3: Loyalty/betrayal

This evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of forming and maintaining coalitions. It makes us sensitive to signs that another person is (or is not) a team player. It makes us trust and reward loyalty, and it makes us want to hurt, ostracise, or even kill those who betray us or our group.

Foundation 4: Authority/subversion

This evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of forging relationships that will benefit us within social hierarchies. It makes us sensitive to signs of rank or status, and to signs that other people are (or are not) behaving properly, given their position.

Foundation 5: Sanctity/degradation

This evolved initially in response to the adaptive challenge of the omnivore’s dilemma (which plants, animals are poisonous), and then to the broader challenge of living in a world of pathogens and parasites. It includes the behavioural immune system, which can make us wary of a diverse array of symbolic objects and threats. It makes it possible for people to invest objects with irrational and extreme values—both positive and negative—which are important for binding groups together.

Wherever people sit on the political spectrum, they will place greater value on certain foundations, and have varying ways of understanding and acting upon those foundations. Haidt uses the example of liberals and republicans in the US. He argues that conservatives often place much greater emphasis on things like sanctity (e.g., of body, of objects, of religious beliefs), authority, loyalty (e.g. to nation), and understand the fairness/cheating foundation and the care/harm foundation in a more localised manner. In contrast, liberals tend to focus more on the fairness/cheating foundation and the care/harm foundation at a more universal level (e.g., human rights, animal rights) and less value on things like sanctity and loyalty.

Haidt used images throughout his chapter on moral foundations in The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. The images assist in understanding how different moral foundations elicit different responses. The image to the left indicates the importance of loyalty to country while the image on the right condemns loyalty to one country.

The framework was designed to enable understanding of how people with opposing views may have built up these moral foundations, and also on how political parties might utilise these moral foundations to attract voters or appeal to/manipulate their audiences.

Case study 2:

This weeks case study explored the history of apartheid and the rise of Nelson Mandela as a voice for human rights and equality. Nelson Mandela and his political party, the African National Congress (ANC), after long deliberation altered their principles of passivity and non-violence in order to organise the use of (certain types of) violence to disband the apartheid regime in South Africa. This dramatic shift in principles required long talks and a review of community values. The change arrived after deciding that passive resistance was not going to be successful in ending apartheid. The case was used to explore our views of ‘when, if ever, is violence necessary?’ and differing forms of protest and the way some forms of protest are demonised while others are glorified. We discussed the difficulties in aligning community values when a moral issue is at stake. The case also required our groups to be able to discuss polarising view points, and listen to one another.

Week 4: Leading within organisations

This week focussed on behavioural sciences, and how implicit biases infiltrate organisational systems, whether this be from how job interviews and hiring processes are undertaken, to how humans naturally judge and make assumptions based on appearance. Professor Iris Bohnet, Director of Women and Public Policy Program, argues that it is difficult to fundamentally change someones mind; that while someone may state they hold no inherit biases, they may subconsciously make decisions based on a bias, without recognising any prejudice. The concept of nudging shifts the structure of organisations in order to remove implicit biases. For example, through an employee hiring process, those selecting the CVs might remove names, gender, photos and where the individual has been to school in order to enable each applicant to be on a level playing field when it comes to the selection process.

Group simulation exercise

Week four saw our working group undertake an hour long online simulation exercise designed by Professor Robichaud. Leading up to the simulation, we were required to write down key values we hold dear, key issues we are particularly interested in, and to choose two or three ‘roles’ to play. Roles included defence and intelligence, legal affairs, party influence and cyber security. The task then required our group to work together to assist the ‘46th president of the United States’ (democratic or republican) in making decisions on certain issues. Before entering the simulation, we learned the ‘state of the nation is’ – how divided it is, how well the economy is doing, whether the people of America trust the government – then from the position of your role we were required to aid the president in making decisions of national importance. The goal by the end was to ensure that the decisions made throughout the simulation have left the country in a stronger position than when we first entered the simulation, this was determined based on the advice you give the president.

The decisions made were often tricky, polarising and called upon our moral integrity. Often we had to make tradeoffs in term of our personal values, maintaining in-party relationships, and maintaining trust with the US people. Teams were required to discuss and debate what advice to give the president, learning how to agree and disagree and understand how different people with different principles and organisational roles might have different understandings of right and wrong.

It was interesting to note that, as a group of three women from Australia and New Zealand, we all found that we agreed on most of the advice we were to give the president. A lot of the issues in the simulation discussed things that have already been progressed in our home countries (for example, one of the questions was whether or not to advise the president on establishing a two-week maternity leave scheme), making it difficult, in some scenarios, to have any deep conversation about the decision-making process.

Week 5: Leading in society

The final week focussed on police departments as organisations that rely on the societies they serve to keep them focussed on respecting social justice and promoting public value – in this case, public safety. Today, in many cities around the world, discrimination against minority groups has been a norm of policing for decades/centuries. Many members of those groups don’t believe that police norms can change, while many members of majority groups don’t believe that police norms should change. We focussed particularly on the New York Police Department (NYPD) in 1993 when Rudy Giuliani became the mayor of New York, campaigning on grappling with the city’s skyrocketing crime rates. Giuliani selected William Bratton as the New York police commissioner, resulting in drastic changes to policing techniques which ultimately resulted in crime rates dropping, but also soaring police misconduct claims and major over representation of minority groups being targeted, stopped by police and arrested. Cornell Brooks, Professor of the Practice of Public Leadership and Social Justice at Harvard, discusses historical systemic racism and its impacts on police treatment of African Americans and minorities and how the concept of ‘cognitive reappraisal’ can help in order to interact or engage with those who are emotionally charged by organisational social injustices. Cognitive reappraisal refers to methods in which one can reinterpret situations to modulate emotional responses. He argues that cognitive reappraisal can enable both police and protesters to separate anger and frustration from the way they react to and engage with one another.

Case study 3:

Week five’s case study looked at the tragic story of the death of Eric Garner by a police officer, which was then followed by a series of other police-related deaths with widespread media coverage led to the Black Lives Matter movement and the explosive controversy of race and policing.

Organisers of the Black Lives Matter Protest in Civics Square Wellington, 14 June 2020. Photo taken by Rachel Thomas RNZ)

The course closed with an online awards ceremony and final words from Professor Robichaud. It was an incredible experience, particularly given that the course was in the lead up to the 2020 American and New Zealand elections, a time that is particularly polarising and volatile. I met people from a range of countries with different backgrounds and careers and it was a truly invaluable and insightful experience being able to discuss so many sensitive issues in a critical and open manner with a diverse group of considerate and passionate people.

My main takeaways from this course were learning the importance of listening to opposing views and being exposed to things that you don’t agree with, fostering communication and engagement among people who do not agree with one another, and above all, celebrating the intricacies of humans learning to live and thrive with one another, and acknowledging that we don’t yet have all the answers to cohesion.

The course did not provide any answers, nor did it encourage participants to take on particular views when it comes to the issues discussed. What it did do was provide a number of ways of analysing these unprecedented and fragmented times in the hopes that these tools might assist further cohesion among organisations and communities. Below I outline a few key takeaways for the Institute going forward into 2021.

Key takeaways for the McGuinness Institute:

- Adaptive problems require adaptive solutions and often those without formal authority have greater capacity to interrogate complex issues and develop creative solutions.

- Major issues such as climate change, gender politics and racism are adaptive challenges with no clear solution. It can be difficult to appeal certain audiences towards goals of universal wellbeing and equality and showing them why these matters are important to them. The unknown nature of what a future where these issues are catered to looks like often makes those who are happy with the current ‘norm’ fear that in order for change to progress, they will have to suffer losses along the way.

- It is important to know your ‘why’ when navigating complex issues. Understanding the morals that drive your decision-making, and why you have honed into this issue is fundamental to driving practical and meaningful action.

- Reasonable people might not always agree with you. Society is made up of multitudes of overlapping and often conflicting ideas and perspectives; it is not binary. Negotiating different values in society requires understanding why people disagree, fostering communication and assisting people in learning how to listen to one another.

A massive thank you to Wendy McGuinness for giving me the opportunity to attend the course. I feel very lucky to have been able to sit in a cyber room with some of public policy’s greatest academic thinkers.

Isabella Smith is the Head of Research at the McGuinness Institute. She joined the team in 2017, spent a year in South America in 2018, then returned to the Institute in 2019 to become the Special Projects Manager, followed by Head of Research in 2020. Isabella completed a Bachelor of Arts with a double major in political science and communications at the University of Otago.

Isabella Smith is the Head of Research at the McGuinness Institute. She joined the team in 2017, spent a year in South America in 2018, then returned to the Institute in 2019 to become the Special Projects Manager, followed by Head of Research in 2020. Isabella completed a Bachelor of Arts with a double major in political science and communications at the University of Otago.